Just Earth News | @justearthnews | 19 May 2017, 03:18 pm Print

Image: Creative Commons

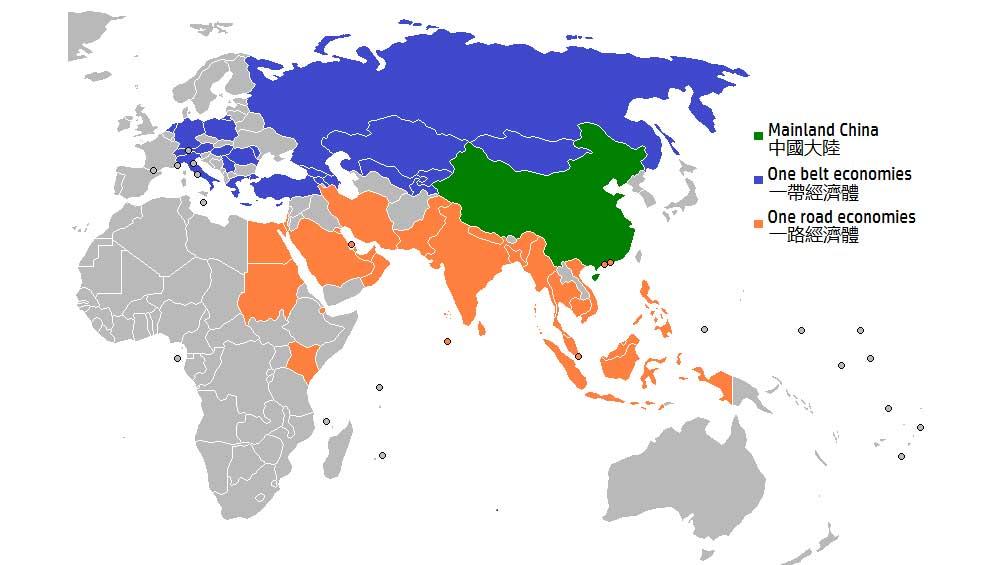

But it is only Sri Lanka, SE Asian countries including Cambodia and few African nations are also heading towards similar crisis from Chinese loans which are offered at a higher interest rate when compared to Japan or India or ADB. Pakistan is no better as the huge sum of 62 billion USD for China-Pakistan-Economic-Corridor has all the potential to spell doom for the already faltering Pak economy.

Sri Lanka’s growing economic engagement with China has generated concern among scholars and policymakers. China has provided Sri Lanka with over US$5 billion between 1971 and 2012. Most of this has gone into infrastructure development, with China investing $1 billion into a deep-water port at Hambantota and billions into the Mattala Airport, a new railway and the Colombo Port City Project. As a country emerging from civil war, infrastructure is crucial in facilitating Sri Lanka’s trade and foreign investment sectors. The World Bank forecasts that Sri Lanka’s GDP growth is likely to grow from 3.9 per cent in 2016 to around 5 per cent in 2017.

Sri Lanka has borrowed billions of dollars from China in order to build domestic infrastructure. Sri Lanka’s estimated national debt is US$64.9 billion, of which US$8 billion is owed to China. This can be attributed to the high interest rate on Chinese loans. For the Hambantota Port project, Sri Lanka borrowed US$301 million from China with an interest rate of 6.3 per cent, while the interest rates on soft loans from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) are only 0.25–3 per cent. Interest rates of India’s Line of Credit to the neighbouring countries are as low as one per cent or even less in some cases. Sri Lanka is facing debt crisis or ‘debt trap’ as some scholars describe it.

Sri Lanka is currently unable to pay off its debt to China because of its slow economic growth. To resolve its debt crisis, the Sri Lankan government has agreedto convert its debt into equity. This may lead to Chinese ownership of the projects finally Lankan decision allowing Chinese firms 80 per cent of the total share and a 99-year lease of Hambantota port caused public outrage and violent protests in Sri Lanka. In addition, Chinese firms have been given operating and managing control of Mattala Airport, built by Chinese loans of US$300–400 million, because the Sri Lankan government is unable to bear the annual expenses of US$100–200 million.

Bangladesh must take lesson from the Sri Lankan crisis before accepting loan from China for the mega projects. China has promised 23 bn USD for projects in Bangladesh and these loans will not be offered at a concessional rate. This may put pressure on Bangladesh economy which has been doing well for the last one and half decades.

Pakistan is heading towards a similar crisis if not worse, according to experts who study China-Pakistan-Economic-Corridor closely. China’s masterstroke in inducing Pakistan into mortgaging Pakistan’s present and future economic prosperity has been achieved by Chinese President Xi Jinping’s announcement in 2015 of the much flaunted $ 46 billion China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The Chinse promise for CPEC is now 62 bn USD. .

Pakistan is heading towards a similar crisis if not worse, according to experts who study China-Pakistan-Economic-Corridor closely. China’s masterstroke in inducing Pakistan into mortgaging Pakistan’s present and future economic prosperity has been achieved by Chinese President Xi Jinping’s announcement in 2015 of the much flaunted $ 46 billion China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The Chinse promise for CPEC is now 62 bn USD. .

Pakistan is being made to take heavy loans from Chinese banks at high rates of interest to finance the CPEC and some experts opine that Pakistan would take nearly forty years to pay back Chinese loans.

Cambodia is one of China’s closest international partners and diplomatic allies, as well as truly under China’s economic and political influence. Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen recently described China as Cambodia’s ‘most trustworthy friend’.

Similarly, Chinese President Xi Jinping described Cambodia as ‘like a brother’ when Cambodian King Norodom Sihamoni visited Beijing in June 2016. China is now Cambodia’s largest military supplier and provider of development aid and foreign investment, having given nearly three billion USD in loans and grants to Cambodia since 1992. A 2016 International Monetary Fund (IMF) report showed that Cambodia’s external multilateral public debt is now at $1.6 billion, while its bilateral public debt with China is $3.9 billion.

While Cambodia and Sri Lanka are different in terms of their geographic location, demography and nature of strategic relations with China, there are some crucial lessons that Cambodia and other small countries in SE Asia can learn to avoid ending up in Sri Lanka’s position. Cambodia needs to diversify its borrowing sources and consider taking loans from multilateral bodies and countries like India and Japan, experts on SE Asian affairs told ET. Cambodia will also need to diversify its foreign policy to include other countries and regional initiatives -- ASEAN and Mekong Ganga Cooperation, suggested experts.

China’s influence in Cambodia is growing as the loans increase. This is already evident, with Cambodia’s decision to ban the Taiwanese flag from being raised in Cambodia. This could be true for other countries in India’s periphery including Maldives. Maldives has leased an island close to Maleairport for 50 years at the cost of $ 4 billionto a Chinese company.

In Africa China may have built stadiums, airports, hospitals, highways and dams across the continent, but these projects left many African countries saddled with debts, environmental conflicts and labour strikes, point out the officials quoted above. In an opinion piece published in the Financial Times in 2013, the Governor of Nigeria’s Central Bank, Lamido Sanusi, alleged that Chinese investment in sub-Saharan Africa smacked of ‘colonialism’, in size and style. Beijing was further accused of holding back a growing African economy by focusing on the pursuit of raw materials, rather than on the creation of local markets and jobs.

“This is nothing but pouring China’s overcapacity overseas. And OBOR wants to further accentuate situation – by pouring Chinese steel and concrete onto local ecology at recipient cost. OBOR is mediaeval mercantilism in postmodern times,” alleged a scholar who has studied China’s foreign policy and forays into Africa for decades.

China has already faced several moments of discomfiture in its attempts to expand influence in Africa. It may be recalled that In 2014, South African President Jacob Zuma cautioned that Africa’s somewhat lopsided trade ties with China were turning out to be “unsuitable in the long term”. In Zambia, in 2015, the government had to take control of a Chinese copper mine after numerous complaints of labour abuse.

That same year, Botswana’s President Ian Khama called for a reduction in new contracts to Chinese companies, citing poor construction and delays. Ghana and Angola too have been unhappy over Chinese products and social tensions due to Chinese approach in ignoring local population.

There are lessons from Sri Lanka, Cambodia and African nations that Chinese loans is a win-win only for Beijing. Loans offered at a steep commercial rate can push developing and middle income countries towards a crisis that they might find difficult to recover from. Besides the recipient countries should insist on infrastructure projects that has benefits for them and not for Beijing.

- World’s top 100 weapons makers hit record $679 billion in 2024

- Asia on the move: Why millions are being driven out by job crises and failing services

- Why Personal Loans are Gaining Popularity Among Millennials?

- Record-breaking economic meltdown in Gaza — UN issues alarming warning!

- Global Industry Summit: Leaders assembly in Riyadh to debate tackling challenges

-1763561110.jpg)